Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5752

Research Article(ISSN: 2690-5752)

An Initiation to [Soft] Urban Archeology: Spatial Arrangement of The Alien ‘Cultural Centers’ and The Interpretation of a Symbolic Pattern in Pre-1953 Coup Tehran Volume 5 - Issue 5

Sahand Lotfi* and Mahsa Sholeh

- Department of Urban Planning and Design, School of Art and Architecture, Shiraz University, Iran

Received:November 03, 2021; Published: November 18, 2021

Corresponding author: November 18, 2021

DOI: 10.32474/JAAS.2021.05.000224

Abstract

This article proposes the notion of ‘soft urban archeology’ by examining the evolution of modernized Tehran under the reign of Pahlavi I as a context for the political rivalry between the Allies during World War II and later until the Nationalization of the Iranian Oil and the Coup d’état of 1953. Firstly, we scrutinized the historical buildings once occupied by the alien cultural centers, which were left unrevealed to the next generations. Secondly, a hidden, symbolic pattern appeared regarding the evidence-based geometry of the points on Tehran’s map of the 1940s. This pattern shows a series of lines connecting the principal points of the British, Soviet, and American cultural centers, which acted as the Big Three delegation offices with different cultural-propagandist endeavors. However, the spatial arrangement of the points unveiled an undeniable similarity with the symbol of masonic rites. As the polemic of masonic presence coincides with the political tumults between 1941 and 1953, this pattern seems to be an esoteric indication of some ignored facts. By prospecting more and reading the evidence through the historical documents, photographs, and confidential reports and memorandums, an exciting interpretation emerges that clears up some of the fateful events that overbalanced the political situation in 1950s Iran.

Keywords:Tehran; Soft Urban Archelogy; Alien Cultural Centers; Symbolic Pattern; Nāderi Avenue; Nationalization of the Iranian Oil; 1953 Coup d’ Etat

Introduction

The tumults of contemporary Iranian history seem to be endless. Political changes during and after the ‘Nationalization of the Iranian oil’ in 1951 have been the subject of significant research and revelations. By the progress of Tehran’s physical expansion in the 1900s’, its traditional structure fetched into an opener and more ‘occidental’ form simultaneous with the discovery of Oil in Iran by the British [1]. Hence the history of Iranian Oil began with the turn of the nineteenth century and later imposed an everlasting curse on the contemporary history of Iran and the Middle East in particular [2]. D’Arcy’s oil concession of 1901 and its consequence along with many historical events like the Constitutional Revolution (1906), the overthrow of the Qajar Dynasty (1925), two devastating World Wars, the fluctuating foreign politics, Reza-Shah’s modernizing plans, and the occupation of Iran during World War II in 1941, prepared an unprecedented political scene [3]. This is a story of antagonism and political rivalry translated into the urban structure of modern Tehran during the 1940s and early 1950s.

With this approach in mind, the current study aimed to reveal a symbolic relation between anchor points, shaping an enigmatic geometry into a symbolic pattern in Tehran between 1941 and 1953. The metaphoric aspect is relevant to the political events of the time. Also, this study has a specific concentration on the relation of the urban structure that emerged after World War II in Tehran with the political evolution of the same period ended up with the 1953 Coup d’Etat, which has not been explored before as an interrelated subject. The particularity of this research is that it examines the relatively recent published confidential documents about the relations between the United States and Great Britain in the ‘Nationalization of the Iranian Oil’ and the later events that led to the 1953 Coup. Also, it explores pictures from the same period and relates them both to an interpretative-analytical approach elaborated by projecting the focal points of the events into a symbolic composition of a geometric pattern leading to the “Symbol.” The photographs used for the purpose is the rare and precious images from the crucial moments of Iran’s contemporary history in the early 1950s’ taken by the Life magazine’s famous photojournalist, Dmitri Kessel [4]. His classic photos have the speaking ability to show hidden parts of the story. The photographs used in this study as a storytelling medium had been partially published in Life magazine’s “Week’s Events” and “Photographic Essays” between 1951 to 1953. These photographs, circulating online during recent years, have attracted many enthusiasts and Iranian History amateurs, being individually narrated or interpreted, some of which completely ignored, not making a coherent and unified story related to the actual events of that period. A powerful and remarkable story could emerge by exploring the depth of the political events and creating a location and event and time-based identification of each photograph. Another photo archives that helped the authors considerably were the exquisite photographs from ‘Photo Vahé,’ a local studio in ‘Nāderi Avenue’ active since the early 1930s [5].

The other side of this research is the translation of events into the location value of each point. As explained through the article, the title ‘point’ represents the geographic position of some institutions or logistic headquarters on the map, closely related to the political events. This presumption gradually led to some more profound interpretations revealing surprising relations between the points, totally compatible with the events and their latent sources and motivations, as well as their symbolic incarnation. The article also tries to speculate on the Masonic presence on the Iranian political scene of the post-Nationalization period. Some authentic deductions are given by re-reading recently published confidential documents and long-time ignored research on the Masonic activities in Iran. Finally, after presenting the irrefutable results of the “occultic approach,” one could still wonder about the significant aspects of the events not been solved until the date.

The Emergence

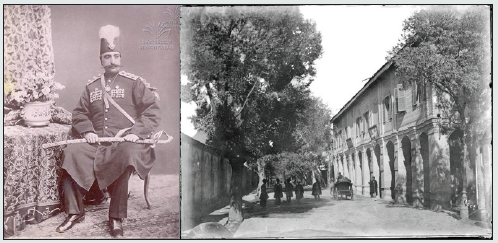

Figure 1: Nasser al-Din Shah Qajar, who ordered the physical expansion of Tehran in 1867 (left). Ala al-Dawla or Ambassadors Avenue was one of the north-facing axes of the expansion plan, in which newly established institutions such as the ‘Hotel de France’ seen in the picture with its arcades were established (right). (Source: Dmitri Ermakov; Antoine Sevruguin).

The urban configuration of the modern Tehran after the inauguration of a new outstretching project for expanding the capital inspired by what Baron Georges Haussmann did for Napoleon III in Paris of the ‘Second Empire,’ made ‘Nasser al-Din Shah’ the first pioneer of European-style urban design in Iran (Figure 1). Establishing an efficient spatial join between the Imperial Palaces or ‘Arg’ and the new northern districts, capable of extending the so-called urbanity towards the new frontiers of the city defined by a new system of fortifications, the ‘Toupkhāneh Square’ was born (Figure 2a) [6]. Employing two south-north axes, representing a formal imitation of either Safavid squares or Renaissanceinspired promenades, these linear spaces, later called ‘Avenues’ or ‘Khiābāns’ as they were named in post-Safavid Persian, served as the first boulevards in its Parisian meaning for the Iranian capital. They were not comparable to their Parisian counterparts neither in scale nor in glamour. One of these avenues is called the Avenue of ‘Ambassadors,’ as it could show the nature of early modernization [7]. This avenue and the adjacent district were the places for new European hotels, photography studios [8], shops, and ultimately a political axis leading towards the foreign Embassies of Great Britain and Tsarist Russia, situated in two extensive gardens [9]. Russia (and the next USSR) and Great Britain were the most influential political powers during the Qajar period and after until World War II [10]. The story could begin in a trendy avenue, a decent one, just coaxing with a long urban corridor, accommodating all the lusters of the so-called “modernity,” flourished in the post- ‘Constitutional Revolution’ era, but far enough to be considered as a part of later political events. That is the way that ‘Nāderi Avenue’ (khiābāni- Nāderi), unfolded at the heart of modern Tehran of the 1920s’ (Figure 2b).

Figure 2: The evolution of Tehran after its outward expansion and the birth of new urban spaces and ‘Avenues.’ (Source: authors).

The Political Scene

By the overthrow of the Qajar dynasty in 1925, the political situation, more than ever, became critical as the global balance began to develop some new polemics and Europe experienced severe political tensions. The time was to plan a more updated political presence regarding the ‘Third Reich’ emerging power in Germany and the ‘Fascist Party’ in Italy. This was a new motivation for obtaining a more acute influence in Iran through a generative political competition. Great Britain was the only power that possessed the valuable oil concession and would do anything to keep it exclusive. Thus the political situation between 1925 and 1941, the year of the occupation of Iran by the Allies and the forced abdication of Reza Shah, is very complicated to be summarized [11]. In short, after the dramatic economic situation of the 1930s’ and the Japanese attack on ‘Pearl Harbor,’ [12] the United States joined the Allies. It began to impose itself as an adequate political power helping the two old Colonialists progress in the war and defeating Nazi Germany [13]. One thing is obvious: the official presentation of the new arrangement of the Allies and the gathering of the three powers in the context of the ‘Tehran Conference’ from November 28 to December 1, 1943. This was the “First Meeting Between the Allies’ Big Three Leaders” and became very crucial to the destiny of World War II, through which Iran became the ‘Bridge of Victory,’ and the young Shah reached the throne [14].

Nāderi Avenue or a Falmboyant Boulevard

Figure 3: Central Tehran and the location of Nāderi Avenue in the merged aerial photos of 25 October 1942, taken by British Royal Air Force (RAF); (B) is the ‘Toupkhāneh Square’ (Source: British National Collection of Aerial Photography, http://ncap. org.uk).

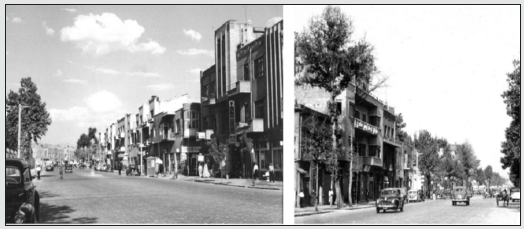

Returning to the main structure of Tehran, a perpendicular line to the previous South-North axes gained significant attention during the 1930s’ (Figure 3). The National Parliament, flourished after the Constitutionalist victory (A) [15], was the climax to the East. Towards West, a new avenue luxuriated with the best examples of a cultural metamorphosis in Tehran’s built environment, was divided into three segments [16]. Initially, the first segment between Bahārestān Square (C) and the intersection of Saadi Avenue or ‘Mokhber al-Dawleh’ (D), named ‘Shāh Ābād’ Avenue (1) was a row for Persian libraries and bookstores from the early 1900s’ considering the educated atmosphere of the Parliament’s environs. The Second segment between ‘Mokhber al-Dawleh’ and ‘Lālehzār’ continues to ‘Ferdowsi’ (ex Ambassadors) Avenue (E), named ‘Istanbul’ Avenue (2), was a center for the European lifestyle, Boutiques, Cinemas, Stores, and Hotels. Finally, the third segment was an avenue bearing the name of ‘Khiaban-i-Nāderi’ (3), known for its intellectual, rather occidental ambiance with its cafés, Hotel, European and American Libraries, Restaurants, photography studios, and well-known stationery mart Shops selling all sort of brand-new fountain pens and accessories. The Avenue was called ‘Nāderi’ after a European-style hotel and cafe soon became famous as a benchmark for Iranian intellectuals. This Avenue became the cradle of the rivalry of the ‘three powers’ called the ‘Big Three’ during the Second World War (Figure 4).

Figure 4: The location of principal buildings related to the activities of the ‘Big Three.’ (Source: Iranian National Cartographic Center, 1964).

The AIOC

The first important spot to this study is ‘Brilliant Passage’ (1), a building near the Nāderi hotel and café (N). Since the coronation of Reza Shah in 1926, considered a British political action [17], Great Britain had sought to secure its political place and the Concession’s benefits by establishing the ‘Information Department’ [18] of ‘Anglo- Persian Oil Company’ (APOC) [19]. Following the change of the official title of ‘Persia’ to ‘Iran’ under the Reza Shah’s government, the company’s name also changed to ‘Anglo-Iranian Oil Company.’ By this time, the headquarters, including the ‘Recruiting Organisation,’ moved to a three-story building named ‘Brilliant Passage’ [20] on the southern frontage of Nāderi avenue in 1946 [21]. ‘Brilliant Passage’ is a typical example of commercial buildings adapted from the European Art-Deco style and Streamline architecture in 1930s’ Tehran (Figure 5) to form the façade and the modern skyline of new avenues with shops and windows on the ground floor and offices on upper floors [22].

Figure 5: Left: Nāderi Avenue and its streamlined and ‘Art-Deco’ skyline in 1948 (the British Embassy white wall is seen at left behind the parked car). Right: and the ‘Brilliant Passage’ with its entrance, windows and balconies in 1949 (the boards of AIOC are seen on the façade) (Source: Image Courtesy of Photo Vahé Archives).

The Building had a half-covered entrance in the middle, followed by a corridor leading to a courtyard or roofless patio serving as an extension for ground floor shops and a skylight facility for the upper floors. As such, the ‘Brilliant Passage’ had four shops opening to the avenue with large windows. The ‘AIOC’ used one of these shops, the one in the east corner, as a showroom for attracting the passingby people with illustrated newspapers, bulletins, and magazines (Figure 6). Also, the young, educated candidates willing to work for ‘AIOC’ headed to the ‘Recruitment Organization.’ The main activity of British clerks took place on upper floors, and there were at least ten full-time “agents” working in Tehran [23]. The AIOCs’ ‘Information Department’ became the first example of a “cultural” organization that could communicate with people and subsequently manipulate public opinion openly [24]. This was when the social atmosphere in Iran was very ambivalent, and different newly emerged political parties made their effort to gain maximum supporters among the citizens [25]. So, a new field of rivalry appeared, and the post-war ‘propaganda’ necessitated. Although there is no explicit information about the internal mechanism of the ‘rival’ organizations, discussed hereafter. Still, the vital matter to the article is the position of strategic points and the spatial arrangement.

Figure 6: The ‘AIOC’ attracts people by illustrated and printed material; in the middle, the entrance leads to the courtyard behind a grid door, and some young people wait for their recruitment interview. (Source: Dmitri Kessel, Life, 1951).

The VOKS

Figure 7: VOKS’ with its modest windows inviting people getting the ‘Последние новости’ (‘Latest News’); and the AIOC building on the other side of the Nāderi Avenue (pointed out by the black arrow) (Source: Dmitri Kessel, Life, 1951).

After the “Red Revolution” of 1917, Tsarist Russia became the ‘Union of Soviet Socialist Republics’ (USSR) and developed its propaganda system, encouraging the nations to uprise against their ‘capitalist’ political systems. So they began to support the foundation of new political parties in countries like Iran with titles generally referring to the ‘Masses’ and ‘laborers’ [26]. To progress in political goals, the USSR founded ‘VOKS’ or the ‘All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries’ in 1925. By the establishment of ‘VOKS,’ the Soviet Union commenced a cultural program primarily aimed to contact other countries’ cultural and artistic delegations. Progressively and ultimately, Western governments recognized this ‘Society’ as an operational branch for the ‘Communist’ propaganda [27]. During the same period, the Soviets’ VOKS found its central office at the corner of the ‘Stalin Street’ (2), named by the Iranians after the ferocious dictator of the USSR, and the ‘Nāderi Avenue.’ This was a strategic corner near the Soviet Union’s Embassy, the ex-Amin-al-Soltan garden or ‘Atābak Park’ during the Qajar period, and concurrently, in the middle of a propagandist battlefield. As the Soviets’ policy required, the building was modest, especially compared to its British counterpart, and the Armenian Church and the Zoroastrian fire-temple at its immediate proximity. A brick covered two-story building with three shop windows on the ground floor stretching all around the street corner with fabric awnings and plywood panels covered with posters of ‘Comrade Stalin’, the ‘Latest News’ or ‘Последние новости’ printed on large format papers and the posters showing the Sovietic unutterable “wellbeing” (Figure 7). There is no public ‘Entrance’ as it’s not allowed for ordinary people to communicate with inside; although there is a door on Stalin street to access the upstairs, it is now evident that the “elite” relations persisted behind the scenes [28].

Figure 8: The ‘USIE’ window with the board showing Dr. Shahriari’s dental clinic in 1951 (Source: Dmitri Kessel, Life, 1951).

The USIE

Figure 9: USIE’s window attracts people in 1950 Tehran. Situated just in front of the Nāderi café, there is an unseen dialogue between them as a propaganda center and a hang out for leftists. In the photo below-right, both Nāderi Café and the ‘AIOC’ building (Brilliant Passage) could be seen on the opposite side of ‘Nāderi Avenue.’ (Source: Dmitri Kessel, Life, 1951).

The Americans, in their turn, established the ‘USIE’ by the end of the War. In the middle of the 1940s’ after defeating Germany in the Second World War, the United States experienced an economic boom, and this was not only economic but social and, most importantly, political. In 1949, Harry Truman set the foreign affairs as his new battlefront and founded the ‘Point Four Program’; A tool for giving technical aids, “learning to live in peace and harmony,” and “compensating” the damages imposed to a third world country like Iran while playing its role as the ‘Bridge of Victory [29].’ For this purpose, the ‘United States Information and Education Services’ (USIE) started its activities in 1949 in Tehran [30]. The emplacement of this new “Service” was not quite a surprise. The Americans chose a new building, architecturally very similar to the ‘Brilliant Passage’ on the opposite side of the Avenue, of course, more significant and more recently built. This building named ‘Gueeve Passage’ was another “Passage,” originally built to be a commercialresidential complex, and at the time that the Americans held the majority of the building, a dentist and a famous trading company and curtain seller were already settled in it (Figure 8) [31]. The American ‘Information and Education Services’ approach was to act more openly or pretend to have a flexible cultural relation and educational aid to the Iranian society. On the ground floor of the ‘Gueeve’ building, facing towards ‘Nāderi Avenue,’ there was a bookshop or, more precisely, a library showroom that was very attractive for the passing-by people, giving free access to books, magazines, and bulletins in English and Persian [32]. The theme of technical, health, and agricultural development is very dominant in the publications. Studying the fantastic photos of this library taken by Dmitri Kessel for LIFE Magazine shows that there was an unbelievable diversity of people, from the new modern generation of well-dressed citizens to homemakers, workers, and peasants, fascinated by this unique venue, although shy enough not to show off vividly (Figure 9).

At this time, a very obvious and bold rivalry between the three “windows” had begun. The ‘USIE’ had another library, active under ‘United States Children’s Library’ situated on the west side of the building, accessed from the adjacent street to ‘Gueeve Passage’ more intimately located. Here female teachers read books and fairy tales for the children, envisaging a profound cultural influence in perspective (Figure10 a & b). The main entrance of ‘Gueeve Passage’ led to a central courtyard in two levels. This was the access to a vast ‘reading hall’ at the end of the ground level, accessible to Americans and Iranian students and intellectuals as well (Figure10 c & d). In 1950 the ‘American Center’ as people called it, also became the headquarters for the American anti-Communist propaganda. On the lower floor of the courtyard, a full array of propaganda bulletin distribution system was organized. Enlisting a bunch of young Iranian cyclists, the daily bulletin or the ‘USA Daily Report’ is distributed in all the capital districts down to the bazaar and the traditional neighborhoods (Figure 10 e to h). The administration or the ‘American Center’ operating mechanism occupies the upper floors of the building in the northern wing, far from the Avenue.

Figure 10: (a and b) The USIE Children’s Library and Public Library in Gueeve Building. (c and d) The Public Library. (e, f, g, and h) The distribution system for Bulletins named ‘USA Daily Report’ from USIE to the Bazaar and old neighborhoods (Source: Dmitri Kessel, Life, 1951).

The Events

Now that the position of the three buildings or so-called ‘Cultural Centers’ has been described, it is time to write about the events that ended up in the 1953 Coup and interpret the spatial relation of the points. The post-war political events in Iran and their consequences directly result from the ‘Three Powers’ hidden activities, but this statement has become a ‘cliché,’ and the reality is much more complicated. Even before the end of the war and after the occupation of Iran, the Soviets began their pro- Communist propagandist activities all over Iran. Profiting the long-lived feudalistic background and landowning system in Iran, Russians manipulate the working classes, peasants, and reformist intellectuals to push the society into a deep social reform and orient the political system towards the USSR [33]. This period, beginning with the overthrow of Reza Shah in 1941 and ending with the unsuccessful assassination plot of the Mohammad Reza Shah in 1949, could be entitled as the period of the ‘Communist Movement’ in Iran.

The apparition of the ‘Tūdeh Party’ and propagation of ‘Socialist Communism’ from early 1942, followed with the ‘Pishēvari movement’ for the independence of Azerbaijan province to join the USSR (1945-46), and the uprising of Kurds and Qashqais (1946), were all a series of events empowering the Socialist presence. Sympathizing with many masses in all regions, especially their longtime fief of the northern provinces, Soviet activities, revealed a shocking number of supporters and helped the representatives of the ‘Tūdeh Party’ to hold eight parliamentary seats in the 14th parliament in 1946 [34]. British officials touring the Caspian reported: “Tūdeh had gained so much influence in Gilan and Mazandaran (northern provinces) that the control of affairs had virtually passed into their hands [35].” The British worried most when they knew that the influential presence of the Tūdeh Party had reached their territories in southern Iran, where they had total control on the oil industry and thousands of oil workers susceptible to the communist propaganda, worked for ‘AIOC’ in Abadan and Masjid-i-Suleman [36]. This was the “Red Line” for the British and accelerated the rhythm of the rivalry game considerably.

A suspicious event of this period was the unsuccessful assassination plot of the Shah on February 4, 1949 [37]. Offended by the act, the Shah, outlawed the Tūdeh Party immediately, forcing them to pay a heavy price [38]. As the leading members of the Tūdeh Party were higher-placed intellectuals and army officers, the situation became critical as Shah banned all their activities, imprisoned and executed an actual number of military and civil members of the Party. From the other side, this was a bonus for the British as they successfully though momentarily pushed out the Soviets from the political scene and deprived them of an expected oil concession in the North. Meanwhile, as Great Britain followed its interests in the oil sector, a series of negotiations took place, without success, during this same period through which the British were optimistic about extending their control as the dominant partner of ‘AIOC [39].’ One of the counterattacks of the Tūdeh Party was the propagation of ‘Anti-Colonialism’ sentiment among their supporters; The ‘AIOC’ became the symbol of abusing the natural resources exploited by the British government, and as the British were trying to marginalize their old rival, they became the primary target for the new ‘Nationalist Movement [40].’

By early 1949, the ‘National Front’ of Dr. Mohammad Mossadeq, then a parliament deputy, suspended all negotiations with the ‘AIOC’ representatives and, carrying on the role of Anti- British militant, demanded the Nationalization of ‘AIOC.’ The “Antics of Incomprehensible Orientals,” as the Britons named Mossadeq, wanted immediate action for the control of ‘AIOC [41].’ The British government made a great effort and tried to convince the Parliament to recognize the renewal of the ‘Oil Concession,’ but this never happened, and the resurrection of ex-Tūdeh members under cover of independent deputies made the condition favorable for the ‘Nationalization of the Oil Industry’ in the Parliament. In this situation, even the appointment of Razmārā as the new Prime did not help. Razmārā dealt with the complicated situation so that all of the three powers felt they could “get enough from the game” despite the tumultuous events [42]. His political position was not so confident, and when in March 1951 resisted against the will of people and the Parliament to nationalize the ‘AIOC,’ he was brutally assassinated (Figure 11 a & b) [43]. As Hossein Alā, an experienced aristocratic diplomat, replaced Razmārā, the tension even worsened, and finally, on March 20th, the Parliament passed the bill of the Nationalization of ‘AIOC’ and Iran entered into a severe conflict with Britain [44]. The British government used the Americans as intermediate to solve the conflict during the upcoming months, but Mossadeq told the famous American envoy, Averell Harriman, “you don’t know how evil they are” (Figure 11 c) [45]. After the ‘Office of National Estimates (ONE) report in 1951, the Britons knew that they were entirely dependent on the Iranian oil in the short term, but the situation was such that they could not win the battle independently.

Figure 11: (a) Razmārā and his family few days before his assassination in March 1951 (b) the interim Prime Minister Hossein Alā in the funeral of Razmārā; (c) and the meeting between Averell Harriman and the new Prime Minister Mossadeq in the presence of Hossein Alā and the Special Envoy’s spouse Ms. Marie Norton Whitney Harriman (Source: Dmitri Kessel, Life, 1951).

The ‘Plot’

A new plot was gradually planned. Besides, many political costs that the Nationalization imposed on Mossadeq as the Prime Minister internationally, from this moment on, Great Britain, that was obliged to withdraw from the official domestic scene of Iran’s politics, decided to manipulate Americans to play a new role for them [46]. In other words, and as Madame de Pompadour had said two centuries earlier, “après nous le deluge!” (after us the flood), they preferred to impose the lost to their rivals too, though implicitly. The “Anti-Soviet” sentiment was a contagious phobia that was well transferred to the Americans [47]. The United States was somehow a newcomer to the Iranian political scene, and this situation pushed them to skepticism and fear from the Soviets in their foreign politics. As some expositors commentate, during the postwar period, Great Britain considered the United States as its main “problem” and counterweight in the region and not the USSR [48], so it is logically strange that the UK suddenly required the US to be a strategic complicit [49]. By the influence of the British government, the United States tried to figure out ‘Iran’s Position in the East-West Conflict’ and soon became fearful of the pro-Communist movements in Iran [50]. Along with other instabilities that occurred after the War, this situation emerged the most famous political conflict of the 20th century, the “Cold War.” Indeed mentioned, “Washington considered the Middle East in general, and Iran in particular, to be among the great prizes in the geopolitical and ideological struggle against the Soviet Union,” and this was after about 175 years of total ignorance towards Iran as a political interest [51]. The Americans presumed that with the Nationalization of oil, “the Iranians will turn to the Soviet Union instead of UK-US [52] for technical advice [53].” The British agreed that domestic politics in “valuable areas” is essential for the international challenge between East and West. After three centuries of Britain-Russia rivalry, now the arena was left to ‘East-West,’ which could clarify the role of those ‘Cultural Centers.’

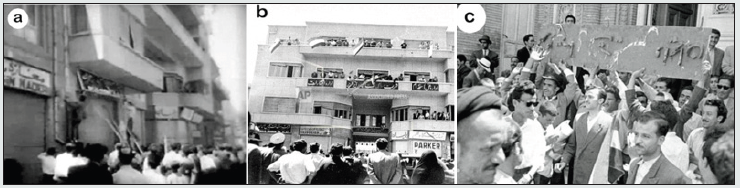

The Americans prepared a new program for ‘United States Information and Education’ or the ‘USIE’ by joining the play’s cast. The dates in which the confidential correspondences proposing the new “cultural” program are sent seem very meaningful regarding the unstable situation of Great Britain [54]. This new program insisted on the ‘anti-communist propaganda, and even proposed making of motion pictures “in the style of Disney” as a “technique of lampooning the Communist System without mentioning it as such [55].” The attractiveness of the Library as the “only source for up-to-date medical and technical books” could also help the propaganda. So, the Americans were softly pushed to a battlefield, not as calm as it first appeared. On 17 June 1951, the people and supporters of Mossadeq and Tudeh Party invaded the ‘Brilliant Passage’ and threw away the billboards bearing the name of ‘AIOC’ ‘Information Organization’ and ‘Recruitment Department.’ During the forthcoming manifestations, the boards reach the Bahārestān Square just in front of the National Parliament (Figure 12).

Figure 12: The breakdown of ‘AIOC’ in June 1951: a) A scene extracted from the ‘World News’ of British Pathé showing the ravaging people tear-down the signs from the AIOC’s ‘Information Department’; b) The Brilliant Passage being occupied by ‘Nationalists’ and their fluttering flags, and c) The AIOC’s board in the hands of Nationalists in front of the Parliament entrance doorway. Source: British Pathé (left) and Associated Press (middle and right)).

A new round of repression towards closing the British centers all over the country began. The revelation of anti-Nationalization missions led by the Britons in “Brilliant Passage” and retrieving the transferred documents to the residence of ‘Richard Seddon’ [56] some days later, serving as proof to the intervention of Britons in the national politics and the manipulation of Iranian politicians, made the government to order the closure of all foreign cultural and information centers outside Tehran. In January 1952, during a confidential telegraph, signed Henderson, [57] it is implied that Mossadeq is “under fire” for not having closed the US consulates and the decision is initially taken for British centers, but to “applying the law equally” the Russian and American centers have also been obliged to close their doors [58]. The twenty months to come were full of vicissitudes of political incidents, and finally, the Coup became operational. Today and almost seven decades after, by reviewing the recently released ex-confidential documents of the 1953’s “American” Coup that tarnished the image of Americans in Iran “forever,” it could be understood that how the Americans got “Entrapped” in a British plot [59].

The Symbolic Pattern

To elaborate the hypothesis of a British top-secret plot to discredit their Soviet and American rivals in the political relationships of 1950s’ Iran, it would be most helpful to get back to the ‘Nāderi Avenue.’ This article has not sought to analyze the political aspects of the events undergone between March 1951 and August 1953 but to give an interpretation related to a symbolic pattern, related to the scenarios that ended up with the 1953’s Coup. In better words, the spatial arrangement of ‘AIOC’ in ‘Brilliant Passage,’ the ‘USIE’ in ‘Gueeve Passage’ and the Soviet ‘VOKS’ on Nāderi Avenue shapes a geometry which tried to be explained here symbolically. After losing the concession and all the benefits from the Iranian oil by the Nationalization, the British sent a new series of conspiracies against the National Government and, above all, Mohammad Mossadeq in person. Indicatively the origin of the hidden activities was still the ‘AIOC’ building or the ‘Brilliant Passage’ (1). The ‘USIE’ was on the opposite side of Nāderi Avenue with an angle of about 45 degrees northeast (3). After being “alerted” by the British, this is where the Americans began their new program of Anti-Communist propaganda and developed a growing phobia for the Russians. The ‘VOKS’ in its turn and, despite many reservations, tried continuing the propagandist role, and the situation of the post-Nationalization period was favorable for such activity [60]. The ‘VOKS’ building at the corner of Stalin Street was situated just at the opposite angle of ‘USIE’ along Nāderi Avenue (2). Now, when we connect points (2) and (3) to (1), a right-angled triangle takes form with the ‘AIOC’ as ‘vertex.’ So the geometry of this setting is intriguing as one might imagine that by the “absence” of the British, the game had become bilateral. However, the role of the “Vertex” is something quite cogitable.

Once the triangle drawn, the second set of spatial relations is traceable (Figure 13). Here, we should introduce some new points on the map. Just between the ‘USIE’ and ‘VOKS,’ there is a narrow and long street, perpendicular to Nāderi Avenue, leading to the main (Southern) Entrance of the USSR Embassy (a). As pointed out in all historical studies, the Soviets were a critical part of Iran’s political game, and their presence had brought all the “difficulties” to the Americans. This gate is the same entrance that the leaders of allied forces crossed through to decide the destiny of World War II under the negotiations of ‘Tehran Conference’ and thus has a considerable significance in the story [61].

Figure 13: Connecting the points makes a right-angled triangle with the ‘AIOC’ Building in the vertex (Source: authors).

By exploring the unknown faces of the political rivalry backgrounds, one should take another fact into a serious concern. There is a long and controversial story about the presence of Freemasons on the political scene of Iran [62]. It is well documented that the British founded their Lodges along with their activities concerning Oil industry in Iran from the very beginning [63]. The Lodge 1324 of ‘Masjid-i-Suleman’ was an English Masonic Lodge specially established for the British ‘APOC’ officials in Ahwaz, Abadan, and Masjid-i-Suleman. As it was a registered Lodge, all its Symbolic ornaments were conserved even after the Nationalization. Despite the critical history of Freemasonry in the latter part of the Qajar period and its “distinguished” members [64], their activity had been diminished considerably during the Reign of Reza Shah, followed by the War and transfer of power in 1941 [65]. It was only in the late 1940s’ that the Masonic activities reintroduced to the Royal Court by the efforts of Ernest Perron, one of the Shah’s close entourages, and the establishment of the ‘Homāyoun Lodge’ in the middle of the Oil conflict could be considered as an undeniable fact showing the critical role of Mason “compatriots” in the political contest [66]. When an eminent Iranian Mason, Mohammad Khalil Javāheri, struggled to establish a new Iranian Lodge, despite the scandalous revelations about the real Masonic intentions made by Razmārā before his sudden assassination and published in ‘Tehran Mossavar,’ a trendy magazine of the time, nothing could stop the course. Contrary to his allegation for the Homāyoun Lodge being a convention to pursue the “humanistic” duty of Freemasonry, the pieces of evidence speak differently. As it has been narrated in an investigated version of the story, the ‘Homāyoun Lodge’ had a close relation to the political events of the Nationalization. The date of its establishment is November 24, 1951; this is a short time after the Nationalization and the entire period of British secret deployment against the National government. Javāheri has explicitly affirmed that the Lodge’s foundation was top-secret, and the founders did not want the ‘Tūdeh Party’ and Russophiles to discover its existence [67]. More surprisingly, during this post-Nationalization period and until the Coup of 1953, it has been emphasized that the Lodge had been running an “Underground” activity [68].

In the perpendicular street to the ‘Nāderi Avenue’ at the end of which there was the Main Entrance of the USSR Embassy (a), there was a building attributed to the Iranian Freemasonry, a secret society dedicated to ‘Anglophile’ elites. The Masonic site was a club, named ‘Hāfez,’ established in its turn, just after the ‘Nationalization’ in 1951 as a private club for the members of ‘Homāyoun Lodge’ to “socialize [69].” By continuing with the previously described geometry, another line could relate the ‘AIOC’ building to the Soviet Embassy just crossing the median of the Hāfez Club’s building (b) (Figure 14). To fully generate the geometry, it is needed to expand the map as broad as to show the geometry’s whole (Figure 15). During the Nationalization, Iranian detective officers discovered that the ‘AIOC’ used the resident of its diplomats and high-ranking guests as a new headquarters to continue their operations. A specific building in the neighborhood later became famous as ‘Seddon House’ (c) [70]. This house was situated not very far from the ‘AIOC’ building in ‘Iradj Alley’ down the ‘Qavāmal- Saltaneh’ street perpendicular to ‘Nāderi Avenue’ (and just in front of Tehran’s St. Peter (American) Church (d), The cradle of the ‘Light of Iran’ Masonic Lodge since its first day in Tehran) [71]. As done for the previous points, another line could be traced from the USSR Embassy Entrance (a) to the ‘Seddon House’ (c) just crossing the ‘VOKS’ building (2). Another point to be focused on is the ‘Sales Department’ of ‘AIOC,’ situated along Sepah Avenue in the administrative center of 1930s Tehran, built during the reign of Reza Shah and in which several Ministries and governmental complexes gradually emerged. After the Nationalization, the ‘Sales Department’ adjacent to the ‘Baq-e-Melli’s Gate’ [72] became a division of the ‘National Iranian Oil Company’ (NIOC) and became an important target for the British secret activities. They made a new intelligence connection by infiltrating a fresh Iranian chairman into the Sales Department [73]. Extending the line that relates the Soviet Embassy to the ‘AIOC’ goes straight down to reach the ‘NIOC Sales Department’ (e).

Figure 14: The Entrance of the USSR Embassy where the ‘Big Three’ once gathered (a) could be connected to the ‘AIOC’ (1) via the heart of ‘Hafez’ club (b), a nest for the Masonic activities during the Nationalization (Source: authors).

Figure 15: Progressing with all the ‘points’ completes the symbolic pattern’s geometry (Source: authors).

Moreover, at the Southern or the lower frontage of ‘Nāderi Avenue’ a few steps from the ‘AIOC’ building to the East, the Nāderi Hotel and Cafe was situated. This very well-known cafe belonged to a family of Armenian immigrants and was a nest for the Iranian intellectuals during the 1940s and 1950s’. Nāderi Cafe was a trendy hangout for the reputable writers, poets, and political activists close to the ‘Tūdeh Party’ and a place for pro-leftist discussions [74]. Considering ‘Cafe Nāderi’ as an anchor point in the geometry, a line with the same angle as the ‘Seddon House’-‘Russian Embassy’- ‘NIOC’ (c-a-e) would relate the Soviet Embassy to it (n), but this line is shorter in length. Therefore, it comes to mind that perhaps we could also extend it out to reach another point. By stretching the line just equally as the ‘Soviet Embassy’-‘Seddon House’ line, it reaches the precinct of ‘Bank Melli’ (the Iranian National Bank) somewhere in the old ‘Bāq-e Ilkhani’ (the former garden). The line lands in a residential zone just adjacent to the former mansion of ‘Aliqoki-khān Sardār As’ad’ (f) [75]. This Mansion, later transformed to the National Bank’s Club, was where some twenty years earlier in 1933, and after the abolition of D’Arcy’s Concession by order of Reza Shah, the negotiations for a new concession were held between Iranian diplomats and AIOC’s representatives [76]; an unfruitful and long challenge for the British, and a motivation for the upcoming act of vengeance. The point (?), crossed by the geometric pattern and situated in a well-sheltered retired by road, remained mysterious [77]. It is imaginable that the house could be a place for those “underground activities” mentioned once by the Grand Master Javāheri. Now that the geometric pattern is complete, the result is symbolically impressive if viewed in the abstract. The abstraction of the geometry shows the ‘Symbolism’ and the components of a well-shaped ‘Square and Compass’ (Figure 16). However, whether by chance or accident, what is observed in this spatial interpretation and geometric form has significant symbolic reciprocity with the historical events of that time. Since this symbol is usually depicted with the letter G in the center, the ‘Hafez club’ location exactly corresponds to where ‘G’ can be placed.

Figure 17: The manifestations start in Nāderi Avenue (a) (the USIE building visible at the top right corner of the picture), and continue to the Bahārestān Square (b), and in front of the National Parliament (c) (Source: Dmitri Kessel, Life, 1951).

By June 1951, the public stage of the ‘Nāderi Avenue’ began to take over a historic role. Different political demonstrations heated the street-life in Tehran, usually by gathering on ‘Nāderi Avenue,’ traversing the West-East axis, and continuing to the Parliament and ‘Bahārestān Square’ at one mile away to the East (Figure 17). The “confusion brought conflict,” and the East-West battle found a champ on the “Avenue [78].” Pro-Communist manifestations overworked the crisis and paraded against the US Propaganda. Reciprocally the police and later the “Gangs of Tehran” or pro- Shah mobs beat up the “Reds” and Pro-Mossadeq demonstrators [79]. The tumults paralyzed the country, and the evil consequences made the Shah, angered by the Nationalists and the Communists, consider the “West” as his only supporter and ally.

The Epilogue

The “Coup” of 19 August 1953 was a disaster for the immature constitutionalism in Iran that turned the Nationalization into a “Big Mistake” and was instead an act of vengeance [80]. As the plot progressed, planned minutely by the “Vertex,” The United States got tricked and became bound to “lie in the bed which had been made” by the “expelled” force [81]. After the assignment of the United States to the “unwanted” Coup project, the operation ‘TPAJAX’ ran as the National Government overthrow action [82]. The Coup was also a big mistake that discredited the Americans in the eyes of the Iranians and led to the US-Iran divide by 1979, even though tremendous help Americans did to improve the Agriculture, Health, and development issues in Iran during the postwar period [83]. More than sixty years later, the Americans officially admitted their role in the Coup, but as far as it concerns the pre-described “Symbolism,” neither Americans nor Russians did most for destabilizing the country’s politics in the upcoming decades since [84]. Today the ‘VOKS’ and ‘USIE’ buildings still exist (Figure 18). Still, their tradesman occupants have no idea of to which degree the contemporary history of Iran had suffered from the historic events that originated in these silent and rusty buildings. While in the case of the ‘AIOC’ building that must have been preserved and potentially reused as ‘Museum of the Iranian Oil Nationalization,’ it was partly demolished in 2014 and then entirely rased in 2020 [85]. “Partly,” because the successors of the ‘Parker’ fountain pens representative, the 80-year-old store at the right corner of the main entrance (Figure 12b), resisted the building’s demolition and redevelopment by the “nouveau-riche” developers and social climbers. While the building had lost three stories, the shop was active to the last moments, covered just by a provisional metal sheet roof. By strolling around the neighborhood, it is hard to imagine that once, ‘Nāderi Avenue’ was the cradle of a fateful overturns due to the cruel thirst for “OIL.”

Figure 18: ‘Then’ and ‘Now’: In search of lost time (from top to bottom: AIOC, VOKS, USIE buildings) (Source: Dmitri Kessel, Life, 1951, authors).

References

- The British geologist George Reynolds was the first man to discover oil at a “remote wilderness spot known as Masjid-i-Suleiman” in 1908. Howard R (2007) Iran Oil: The New Middle East Challenge to America, London, IBTauris & Co. Ltd, p.1. In this book, Roger Howard discusses the importance of Iran’s natural resources to the west even today, New York, USA.

- Ross M (2012) The Oil Curse: How Petroleum Wealth Shapes the Development of Nations, Princeton University Press.

- Peter J Beck (1974) The Anglo-Persian Oil Dispute 1932-33. Journal of Contemporary History 9(4): 123-151.

- Dmitri Kessel (1902-1995) was a Ukrainian-American photojournalist who covered most of the Iranian Royal events and ceremonies in the 1950s and 60s and took very precious photographs from everyday life and political manifestations of early 1950s' Tehran, Iran.

- The authors had acquired these photographs between 2006 and 2014 from one of the descendants of the first founder and the current owner of the Studio.

- ‘Toopkhāneh is the Persian title for ‘Artillery,’ and in English, the name of this square could be translated as ‘Cannons’ Square.’ This sizeable rectangular space (330'×730’) was founded in 1867 with six ornate gates opening to the Royal Palaces in the south (Bāb-e-Homāyoun and Nāserieh), New Avenues on the north (Lālehzar and Alā-o-Doleh) and two functional roads leading to the public hospital (Marizkhāneh) in the west and the first gas lighted street (Tcherāgh-Gaz) in the east, was an amalgam of western official spaces and the oriental introverted space and Safavid Meydan’s. Mohammadzādeh Mehr, Farrokh (2003). Tehran’s Cannons’ Square: a Glance at the Evolution and Continuity of Urban Spaces [in Iran], Tehran: Payām Simā.

- ‘Khiābān-i-Ambassador’: While inaugurating, ‘Mirza Ali Asghar Khan Amin al-Soltan’ titled ‘Atābak’ (1858-1907) was the powerful chancellor and his mansion situated between the two new avenues, and thus the Avenue was named after him. The northern part of the Avenue adjacent to the ‘Ilkhani’ Garden (a large garden designated by Mohammad Shah Qajar (1808-1848) as the Qajar’s Tribe Patriarch) was called ‘the Avenue of Ilkhani Garden.’ After the decline of Amin-al-Soltan, the Avenue’s name changed to ‘Ala-al-dawleh’ (1866-1911), whose house was situated along the Avenue. Finally, by the coronation of Reza Shah in 1926 and for commemorating the millennium of Ferdowsi, the Iranian epic poet, this Avenue was called ‘Ferdowsi’. ‘Ambassador’ was a name given to the Avenue by the foreign inhabitants of Tehran. Motamedi, Mohsen (2002). The Historical Geography of Tehran, Tehran: University Press Center.

- Photography was a new phenomenon, and in this epoch, two studios were open in the 'Ambassador' or 'Ala-al-Dawlah' Avenue: The Studio of Antoin Sevruguin (1830-1933) and the one of Mehdi Ivanov aka 'Russi-Khan' (1875-1967). During the 'Constitutional Revolution,' the studio of Sevruguin was sabotaged by the mercenaries of Mohammad Ali Shah in 1908. In his turn, Russi-Khan was the first person who introduced the Cinema to the Iranian spectators and turned his studio partially into a movie hall as in 'Farang' (the title given to France by Qajars as the emblem of western civilization). Yahya Zoka' (2006). History of Photography and the Pioneer Photographs in Iran, Tehran: Elmi-va-Farhangi.

- The Russian Embassy holds a vast and verdant garden called ‘Atābak’s Park’ after ‘Mirza Ali Asghar Khān Amin-al-Soltan’ (1858-1907). As mentioned in different sources, this garden was one of Tehran’s most extensive and most beautiful gardens designed in a European style. After the passing away of ‘Atabak,’ due to his debts, the heirs gave the garden as mortgage to a Zoroastrian banker and Exchange director, and by the bankruptcy of the latter, the park was given to the “Banque d’Escompte de Perse” of Russia. This garden later became the Russian Embassy despite a prolonged disagreement between the Iranian and Russian Governments. Hosseini Bolaghi, Seyed Hojjat (2007). The Concise History of Tehran (Gozideye Tarikh-e Tehran), Tehran: Mazyar Publications pp. 101-102.

- During the 18th century, they cooperated to overthrow the French monarchy, and after the French Revolution, the Russians and the British became strategic allies, especially in defeating Napoleon 1, marginalizing its political influence in ‘oriental’ territories and monopolizing their role in Iran. Although the French, Belgians, and Austrians, among others, had some counselor roles in establishing modern militarism and educational facilities, the primary influence remained for those two all along the Qajar’s period. Ingram, E., “Great Britain and Russia. Great power rivalries, University of South Carolina Press William R. Thompson, ed. (1999) pp. 269-305.

- Abrahamian E (1983) Iran Between Two Revolutions, Princeton University Press; and Abrahamian E (2008) A History of Modern Iran, Cambridge University Press, USA.

- (1991) The "Japan's Achilles' Heel" as Daniel Yergin describes in his book "The Prize, The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power. The British awaited for the cooperation of the United States in the Second World War from the beginning: "The war for which they had been waiting and preparing had, at last, begun." Daniel Yergin, The Prize, The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power, Simon and Schuster pp. 351.

- Beschloss M R (2002) The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman and the Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1941–1945. Simon and Schuster.

- River Charles (editors) (2016) The Tehran Conference of 1943: The History of the First Meeting Between the Allies' Big Three Leaders During World War II, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- The ‘National Parliament’ was built in a vast and well-placed terrain belonging to ‘Mirza Hosein Khan Moshir od-Dowleh’ called ‘Sepahsālār’ (1828-1881), the Chancellor of Persia under Naser al-Din Shah between 1871 and 1873. The architect of the building is ‘Momtahen-al-Dawleh, Mirza Mehdi Khān Shaghāghi’, the first western-educated Iranian architect who introduced the European architectural style and synthesized the traditional Iranian and European Styles to make a new ‘Eclectic’ style remembered as ‘Tehran School’. The west façade of the building, in Baroque style, was completed by ‘Jafar Khān Me’mar-Bashi’ ‘the Architect’ (1861-1934) in 1924. Amir Bāni Masoud (2009). Iranian Contemporary Architecture, Tehran: Honar-e Me’mari Gharn, pp. 108-112. The Square in front of the Parliament or ‘Bahārestān’ Square is also a modern urban space very present in the maturation of Iranian politics and controverted “Democracy.”

- Khorshidi Kh (2012) Those Good Old Days: Tehran (Ān Rūzegārān-e Tehran), Tehran: Ketābsarā

- Mohammad Gholi Majd calls the appointment of ‘Reza’ to be the founder of a new dynasty named ‘Pahlavi,’ a British Coup d’Etat. See Majd M Gh (2001) Great Britain and Reza Shah: The Plunder of Iran, 1921-1941, University Press of Florida Chapter 3.

- In Persian, and to avoid any sensitivity about all that could be related to “Information,” they translated it as ‘Publication Department’ (Edāreh Enteshārāt). Iran’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (1951). The Documents on Oil (Asnad-e-Naft), Department of Publications and Advertisement.

- The ‘Anglo-Persian Oil Company’ (APOC) was active under the same title until 1932 when Reza Shah suspended the ‘Concession’ and, after a long series of negotiations, finally signed a new concession on April 29, 1933, for sixty years. They changed the name of the company due to changing the name of the country from ‘Persia’ to ‘Iran’ in 1931 to ‘Anglo-Iranian Oil Company’ or (AIOC). Jacques de Launay, Jean-Michel Charlier (1985). Histoire secrete du petrol 1859-1984, Paris: Presses De La Cite, translated to Persian by Jāleh Ālikhāni (1990) Tehran: Khāmeh Publications pp. 133.

- Derived from the French word ‘Passage, this was an imported title for the buildings having a corridor-shaped space within them with a series of shops opening to the corridor as it was common in Paris under the same name. Contrary to the Parisian Passage, these buildings usually did not have the role of a passageway.

- The first director of this department was Laurence Lockhart (1890-1975), a scholar, photographer, and writer who was opposed to the espionage activities of the department. "One of his most engaging duties at the company was his assignment to write a history of the company for private circulation…. In 1939, Lockhart published Famous Cities of Iran, collecting his travel accounts in Iran that had originally appeared in The Naft magazine (AIOC's in-house journal)".

- This Architecture introduced the spatial perception of ‘Avenue’ and created an actual ‘Enclosure’ for the linear spaces in modern Tehran. For further discussion about the modalities of this Iranized ‘Modern Architecture’, see Kiani, Mostafa (2005). The Architecture in the Period of Pahlavi the 1st (Reza Shah), Tehran: Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies.

- Steinberg S H (1950) The Statesman’s Yearbook. Macmillan and Co. Ltd, London, UK pp. 1290-1291.

- Lockhardt openly criticized the ‘Information Department’: “This department has not been organized to inform but to give false information to the Iranian people.” He has dismissed from service afterward. See Raeen, Esmaeil (1979) The Secrets of Seddon’s House p. 28.

- The Tudeh Party was very successful in this task and in the meetings held in ‘Baharestan Square’ a crowd of up to 100.000 people has been reported. Azimi, Milād (2015) Pir-e Parniān Andish (the Silky-Thinker Oldman) Tehran: Sokhan Publications p. 1189.

- The first title used in the North of Iran and became a surname for many was ‘Ranj-bar’ (painstaking), referring to the pains suffered by workers, peasants, and the masses.

- In the revolutionary atmosphere of the 1940s,’ many Iranian artists and intellectuals participated vibrantly in the ‘Cultural’ programs of VOKS. The list is very long, but Khaleghi, a great Iranian compositor and musician, was the editor of ‘Payam-e-Novin’ (the New Message), a pro-communist magazine published by VOKS and directed musical programs and concerts for the Society. Ibid pp. 472.

- Anvar Khamei, in his ‘Political Memoirs,’ writes that the Soviets were seeking to join ‘National Personalities’ to the new pro-communist activities through cultural relations of VOKS. Khamei, A. (1993). Political Memoirs, Tehran: Goftār Publications p. 247.

- Committee on Foreign Affairs (1949) “Point Four: background and program (International Technical Act of 1949)”. Department of State, Washington, USA.

- ‘USEI’ Services, a title only seen on the billboards of the “American Center” (the name given as a translation for ‘American Cultural Institute’ or Kānoun-e Farhangi-e Āmrikā) of Tehran until 1953 and afterward in the ‘Confidential Documents’ of US Propaganda released to the public six decades after the Coup of 1953.

- The Parto Trading Company had its office, and Dr. Ardeshir Shahriari had established a dental clinic; his name and address still exist in the Iranian Dentists' Directory database.

- On the entrance door of USIE, these titles are visible: ‘Cultural Relation’, ‘Voice of America’, ‘Public Affairs,’ ‘Library,’ ‘Press Section,’ and ‘Film Section.’ In a document of August 19, 1950, an “intimate working relationship” between the Voice of America and Radio Tehran was reported. National Archives. Record Group 59. Records of the Department of State. Decimal Files pp. 1950-1954.

- Pickett James (2015) Soviet Civilization through a Persian Lens: Iranian Intellectuals, Cultural Diplomacy and Socialist Modernity 1941-55. Iranian Studies 48(5): 805-826.

- Shahbazi, Abdollah (ed.) (1993) The Memoires of Iraj Eskandari, Tehran: Center for Political Researches and Studies, p. 147. Iraj Eskandari (1908-1985) was the first Secretary-General of Tudeh Party pp. 62-63.

- Abrahamian Ervand (2008) A History of Modern Iran. Cambridge University Press, New York, USA pp. 109.

- The Iranian writer, Ahmad Mahmoud, in his novel Hamsāyehā (the Neighbors), describes this period of political life in the province of Khuzestān as complexity of tragic and real-life of poor workers sympathizing with the Tudeh Party and holding pro-communist meetings. This novel has been translated into English; See Ahmad, Mahmoud (2013). The Neighbors, Translated into English by Nastaran Kherad, The Center for Middle Eastern Studies, The University of Texas at Austin, USA.

- This happened during an official visit commemorating the 15th year of the establishment of the University of Tehran. Dr. Aliakbar Siāssi, then the Dean of the University and the closest witness to the scene, has written about this incident in his memories as a tragic and portentous incident. The assassin, Nāsser Fakhr-Ārāyi, a “journalist,” was shot to death, and after that, all was attributed to the Tudeh Party, and The University fired a list of Academic members close to the Party shortly after. Siassi, Aliakbar (2008). The Report of a Life (Gozāresh-e Yek Zendegi), Tehran: Akhtaran Publications pp. 218-226.

- The wide range of arrests of Tudeh Party’s leaders and the restrictions, trials, executions, and imprisonment (Khameyi, p. 715-717) that later turn into a ‘Legacy’ (Alavi, Bozorg (2009). 53 Nafar (Fifty-Three People), Negāh, Tehran, Iran.

- The intervention of some influential Parliament members such as Hussein Makki (1911-1999) “led a long filibuster against the Supplementary Agreement so that the bill would not be voted on until the sixteenth Majles, where Mossadeq hoped to have more supporters” (Abrahamian, Ervand (2013). The Coup: 1953, the CIA and the Roots of Modern US-Iranian Relations, New Press, New York , USA pp. 49-50.

- This was the “Zeitgeist” of those days; The “Socialist movement” was followed by a “Nationalist” one, and this reality could be seen in many writings and memories of the time. See Tolooei, Mahmood (2010). Tehran in the Mirror of Time (Tehran dar Ayinēye Zamān), Tehran Publications, Tehran, Iran pp. 400-401.

- Koch Scott A (1998) The Central Intelligence Agency and The Fall of Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadeq, August 1953, Washington DC: CIA History Staff p. 5

- Abrahamian states that Razmārā was the enemy of British and had a tendency for Russians and leftist officers (Abrahamian, 1983:229); Department of State (2017), Van Hook, James C. (editor), Foreign Relations of the United States 1952-1954, Iran, 1951–1954, Washington DC, USA p. 16-17.

- The article "Dark Days in Iran" in the Life Magazine of March 26, 1951, reveals the "grave worries" of West after the murder of the "wise premier" pp. 44-45)

- Mossadeq became Prime Minister, and from the very first moment, "Great Britain made its greatest effort to overthrow the National Government and bring a bully but submissive government to power." See Movahed, Mohammad-Ali (1999). The Nightmare of the Oil (Khab-e Ashofte-ye Naft), Karnameh Publications, Tehran, Iran.

- The hope for oil peace “dwindles” as the United States special envoy W. Averell Harriman (1891-1986) “Tries to Calm Iran”. Life, July 30, 1951, pp. 24-25.

- As it has been described in an article dated March 16, 1953, the encounter between the two governments pointed out as the “Anglo-American Job” would be a policy to “deal with the reconstruction of the broken economy of the Western World”: Life, March 16, 1953, pp. 34.

- Bayandor, Darioush (2010) Iran and the CIA: The Fall of Mosaddeq Revisited, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, USA pp. 35.

- Farmanfarmaian Manucher, Roxane Farmanfarmaian (1999) Blood and Oil: Memoirs of a Persian Prince, translated to Persian by Mehdi Haghighatkhā Tehran: qoqnoos Publications p. 297.

- It seems that the old formula of ‘Divide and Rule’ still worked as a good tool in the hands of British diplomacy.

- National Intelligence Estimate (1951) Iran’s Position in the East-West Conflict, CIA: Washington DC, 5 April 1951.

- Koch Scott A (1998) p. 1

- The United States officially, but confidentially estimate itself as the UK ally, Bingo!

- Department of State (2017) p. 18.

- The date of the correspondence of the USIE Public Affairs Officer, Edward C. Wells, to the Department of States considering the “Priority Aims and Objectives of the USIE Program in Iran Calls for Enhancing US Prestige and Demonstrating Communist Fallacies” Coincides with the Nationalization and the Mossadegh’s Government getting started. Circular Airgram of April 5, 1951. National Archives. Record Group 59. Records of the Department of State. Decimal Files 1950-1954.

- United States Embassy, Iran Cable from Edward C. Wells to the Department of State. "Motion Pictures--The Film Two Cities," May 16, 1950, National Archives. Record Group 59. Records of the Department of State. Decimal Files 1950-1954.

- “In June 1951, when the Iranian authorities searched the home of the head of the AIOC’s office in Tehran, Mr. Richard Seddon, and found many incriminating files. Mossadeq now had proof that the AIOC had interfered in Iranian politics”. Henniker-Major, Edward (2013) “Nationalisation: The Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, 1951 Britain vs. Iran”, Seven Pillars Institute Moral Cents Vol. 2 Issue 2, Summer/Fall pp. 16-34

- Henderson, Loy W., Ambassador to Iran, September 29, 1951–December 30, 1954. United States Embassy, Iran Cable from Loy Henderson to the Department of State. [Closure of Provincial Foreign Cultural Centers], January 30, 1952, National Archives. Record Group 59. Records of the Department of State. Decimal Files, 1950-1954.

- The VOKS centers in other cities and provinces were forced to close after the terrorist attack on the Shah in 1949, but they re-opened after a while. This new order of 1952 had different motivations.

- Department of State (2017), Van Hook, James C. (editor), Foreign Relations of the United States 1952–1954, Iran, 1951–1954, Washington D.

- The memory of the terrorist attack against the Shah was highly influenced and fell into oblivion by the ‘National Movement’ mediatized by the Tūdeh Party, and the demonstrations held in central Tehran culminated in the events of ’30 Tir’ (21 July 1951), from Nāderi Avenue to the Parliament in Bahārestan Square, the previously explained transversal axis.

- As named in the ‘British Pathé’ report of the conference.

- The presence of this ‘Secret Army’ among the Iranian politicians and influential personalities had been a polemic subject. Accordingly, decrypting the history of Freemasonry in Iran was a taboo subject that few had only contemplated.

- Algar H (2006) An Introduction to the History of Freemansonry in Iran. Middle Eastern Studies 6(3): 276-296.

- There is a great number of high-ranking Aristocrats, Politicians and Royal affiliates in the list. See Raein, Esmail (1978). Masonic Lodges and Freemasonry in Iran, vol. 2, Tehran: Amir Kabir. In this Volume, Raein gives a long history of the Freemasonry during the Qajar period and the summarized biographies of famous Iranian Masons including Princes, Minsters, Landlords, clergymen, Journalists and other socially dignified personalities.

- Mohammad Khalil Javāheri, the founder of ‘Homayoun Lodge,’ says that the Prime Minister of the World War period, Mohammad-Ali Foroughi told him about the decline of the Masonic activities after 1930. Raein, Esmail (1968) p. 6

- As Hussein Fardoust, former General and close friend to the Shah from childhood, narrates in his memoirs, ‘Ernest Perron’ (it is written ‘Proun’ in the English translation), employed just “before the start of the academic year,” was spying for the British, and after the young Shah’s return to Iran, he accompanied him as an influential person in the Court. Fardoust writes about how he was introduced to the Master of Freemasonry in Iran (who he later discovered that was no one but Mohammad Khalil Javāheri) by Proun in a House in ‘Nāderi’ Street (he writes ‘street’ instead of ‘Avenue’ as it is common in the Persian language). This “Trouble-Maker” as Fardoust describes, helped the Freemasonry during the Nationalization and after that until the Coup and died in 1961. Fardust Hussein (1999) The Rise and Fall of The Pahlavi Dynasty, translated and annotated by Ali Akbar Dareini, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers pp. 95-96.

- Raein, Esmail (1968) p. 13

- Ibid p. 27

- This Club, later on, was sustained as an “Athenaeum” named “Hafez Literary Association”; a backup for the collapsed ‘Vertex.’

- Richard Seddon(1951) The Company’s Chief Representative in Persia. Sydney Morning Herald, p. 3.

- Raein (1968) The ‘Light of Iran’ Masonic Lodge, founded in Shiraz by the British and Indian officers of the South Persia Rifle (SPR) in 1919. It closed down in 1921 after the termination of the SPR but resumed its operation in Tehran for the benefit of the British and other foreign nationals in November 1922” p. 42.

- The historical gate of a former "Champs de Mars" was considered to become a large "public garden" but later transformed into a governmental complex. See Hosseini Bolaghi, Seyed Hojjat (2007) the Concise History of Tehran (Gozideye Tarikh-e Tehran), Tehran: Mazyar Publications pp. 62-63.

- Raein, Esmail (1979) The Secrets of Seddon House, Tehran: Amir Kabir Publications p. 37.

- The vibrant memoirs of the famous poet Houshang Ebtehāj (Sāyeh), one of the survivors of those tumultuous years about his partisan friends and their gatherings in Nāderi Café. See Azimi, Milād, and Tayeh, Ātefeh (2012) Pir-e Parniān Andish (the Silky-Thinker Oldman), Tehran: Sokhan Publications (1): 171 &190.

- One of the prestigious members of the first Masonic Lodge during the reign of ‘Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar’ (1853-1907) Raein 2: 54.

- Afshar Iraj (ed.) (1989) The Stormy Life: Memoirs of Sēyed Hassan Taghizādeh (Zendegi-e Toufani), Tehran: Elmi Publications p. 238-239.

- As we could not gather further information, the sizeable aristocratic house visible on the aerial photo of 1942 was demolished a long time ago to become a parking lot for the ‘National Bank’s Hospital.’

- See “Confusion Brings Conflict, blood to Iran”, Life, March 16, 1953, pp. 32-33.

- Folks gave a nickname to the groups of rabbles and mob led by a well-known bully named Shaban Jafari. “Shaban Jafari, commonly known as Shaban the Brainless (Shaban Bimokh), was a notable pro-Shah strongman and thug.” See Durham R B (2014) False Flags, Covert Operations & Propaganda, Lulu.com, p. 264.

- Safayi, Ebrahim (1992) The Big Mistake: The Nationalization of Oil (Eshtebāh-e Bozorg: MelliShodan-e Naft), Tehran: Ketābsarā.

- It is pronounced that the 1953 Coup is a plan imposed on the Americans by the British. In the U.S. Department of State's "top secret security information" document of November 26, 1952, a Coup d'Etat in Iran is proposed by the British to replace Mossadeq's government with a more "reliable" one with the condition that the U.S. cooperate. And, remarkably, the Americans in this stage of events predict the long-term disadvantages of such action. In the end, it recommends that the U.S. "would prefer not to enter into combined planning on this course of action at this time." National Archives, Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, 1950-54 Decimal File: 788.00/11-2652; A week later and In the U.S. Department of State's "top secret security information" Memorandum of Conversation of December 3, 1952, the British have been convincing the Americans by accentuating the danger of Communists and the relation between Mossadeq and the Tudeh Party. This process progressed so that finally the UK-US "Cooperation" turned into an "American Coup," National Archives, Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, 1950-54 Decimal File: 788.00/12-352.

- For further information, see Wilber Donald N (1954) Clandestine Service History: Overthrow of Premier Mossadeq, November 1952-August 1953, Date Published October 1969.

- Petherick, Christopher (2006) The CIA in Iran: The 1953 Coup and the Origins of the US-Iran Divide, American Free Press, USA.

- Iran 1953 State Department Finally Releases Updated Official History of Mossadeq Coup; “For decades, neither the U.S. nor the British governments would acknowledge their part in Mossadeq’s overthrow, even though a detailed account appeared as early as 1954 in The Saturday Evening Post, and since then, CIA and MI6 veterans of the coup have published memoirs detailing their activities”.

- The photo shown in Figure 18 is taken before the demolition of ‘Brilliant Passage.’

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...